Agriculture’s Troubled Waters

Growing up in New England and being exposed to the wilderness as a young Boy Scout, I thought all streams had soap suds in them. I believed nobody could drink water from a stream but only from a faucet. It was taken for granted that polluted streams were a necessary byproduct of the expansion of manufacturing during the previous decades.

Since that time, rivers and streams have gotten cleaner in New England and in the U.S. due to the Clean Water Act of 1972 which regulated point source pollution. In the subsequent decades, other laws were passed at both the federal and state levels to address non-point sources of pollution and to set water quality standards.

Today, most attention is focused on the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) of permitted contaminants in water, especially in the context of watershed management. States are being tasked to implement remediation plans in response to their TMDLs for pollutants. Since the agricultural lands are non-point sources, they have come under intense scrutiny because of fertilizer practices that introduce nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus into ground water.

In recent years, water quality has gotten more attention in many states due to the practice of “hydraulic fracking,” which uses large amounts of water, sand and chemicals in the deep drilling for natural gas. Because of our nation’s past experience with water quality and industrialization, questions have been raised about the long-term effect of fracking near streams and other water bodies.

I started this article talking about pollution because water quantity has never been a big concern in the past in the U.S. Yes, there have been significant droughts affecting parts of the country. But the affected regions always bounce back over time to normal precipitation patterns.

That said, there have been number of disquieting trends in weather and water usage that, when coupled with pollution issues, present a number of future challenges to agriculture. Before addressing these challenges and possible solutions, a few facts may be in order to put everything in context.

Weather is on the forefront of everyone’s mind because of the extreme events being experienced this winter not only in the U.S. but around the world. An unusually dry winter is contributing to persistent dry conditions in the Southwestern U.S., while the Midwestern and Northeastern parts of the country have been dealing with frigid cold and above normal moisture. Weather terms like “polar vortex” are becoming part of the everyday lexicon. In recent years, warmer summers are becoming the norm for most of the country.

The drier conditions have resulted in record fires and declining snowpack in the Rocky Mountain States, while recurrent, high frequency moisture has both hindered and helped the Northeastern states. Globally, the story is the same. While Brazil is baking in the Southern Hemisphere, Great Britain is experiencing widespread flooding and China is facing its coldest winter in decades.

All these extreme weather events are occurring at a time when the global population is rapidly increasing along with its competition for water, energy and food resources. It is not hard to understand that if the snowpack declines in the Rocky Mountains, then there are less seasonal headwaters to feed rivers and reservoirs. With diminishing water resources, distribution must be prioritized among people, manufacturing and agriculture. Historically, this competition for resources results in people needs coming first, followed by protecting manufacturing because of jobs, and, lastly, agriculture.

The snowpack also affects the long-term viability of aquifers located beneath states east of the Rocky Mountains. Since it takes many years to replenish aquifers with snow melt and seasonal rain, these water reserves, like the Ogallala aquifer, can be viewed as a non-renewable resource. The intense mining of these reserves through irrigation has put certain productive agricultural lands at risk of having no water in the future.

Besides quality concerns and the competition for quantity, there is water usage. Since there are varying kinds and amounts of natural and manmade chemicals and particulate matter, water may be safe for one type of use, such as watering a lawn, but not for another, such as drinking.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has addressed usage head on by developing indices that range from 0 to 100 where the low end is poor and the upper end is excellent. Examples of usage indices are the Drinking Water Quality Index (DWQI), a Health Water Quality Index (HWQI), and an Acceptability Water Quality Index (AWQI). The purpose of each index is to give the public some relative measure of quality for a particular type of use, such as drinking.

Separating sources of water based on their usage can be helpful for a community. Recycled water leaving a wastewater treatment plant can be safely used for irrigating vegetation. The recycled water saves money for a landscaper and at the same time reduces the demand for drinking water. While salinity and alkalinity are commonly tracked in irrigated agricultural soils, an unknown number of exotic and unreported chemicals may be present in some underground water. Over time, agricultural usage of water will come under increased scrutiny by discerning consumers, who will want to know where crops are grown and with what water source.

The water challenges facing agriculture are on several fronts. First, growers near populated areas have to compete with people and businesses for water resources. This is especially true in regions experiencing prolonged dry conditions. Second, in high competition areas, growers may have to settle for recycled or brackish water as sources for irrigation. Third, as farmlands are targeted as sources of non-point water pollution, especially in sensitive watersheds, growers may be enlisted to participate in control programs. Fourth, changing weather patterns, whether short or long term, that result in excessive heat and/or drought conditions may force growers to scale back their operations or switch to less productive crops.

Lastly, downstream processors and consumers who are conscious about where and how crops are grown may demand records of production practices including the source, amount and quality of water.

While there are challenges, there are solutions. One solution is the genetic modification of plants to strive in brackish conditions or use less water while maintaining the same amount of growth. A second is to use irrigation equipment and practices, such as schedules, to conserve water. A related third solution is to use soil sensors or imagery to zone irrigated fields for variable rate applications of water. Variable-rate applications may use the same amount of water as applied to a whole field, but deliver less moisture in some zones and more in others based on the pattern of crop growth across a field. A fourth solution is deficit irrigation which is designed to sustain crop yields while saving water.

Solutions outside of irrigation include the use of natural and artificial surface covers to retard soil evaporation and thus conserve ground water. Also, the leveling of land to minimize slope runoff, and the use of basins to catch runoff, may also be employed. There are many other innovative solutions for water conservation on a farm, but choosing them depends on the crop, its geography, surrounding environment, water source and production practices.

All agricultural stakeholders, be they individuals or organizations, can be part of the water solution. ZedX, Inc., my employer, is an information technology company that has been developing information-based products and services for the agricultural community for over 26 years. The company strives to give growers and their trusted advisors a more holistic solution for water management by providing models and decision-support tools that range from multi-county watersheds down to a single irrigation pivot.

By inputting virtual local weather data into a soil moisture budget and coupling it with a crop development model as part of an irrigation schedule, daily recommendations can be made as to how much water needs to be applied to a field. Since precipitation and evapotranspiration are accounted for in a schedule, irrigation can be withheld when ground water is replenished through rainfall. This withholding of irrigation not only translates into a savings of water but also into a savings in dollars for energy and labor.

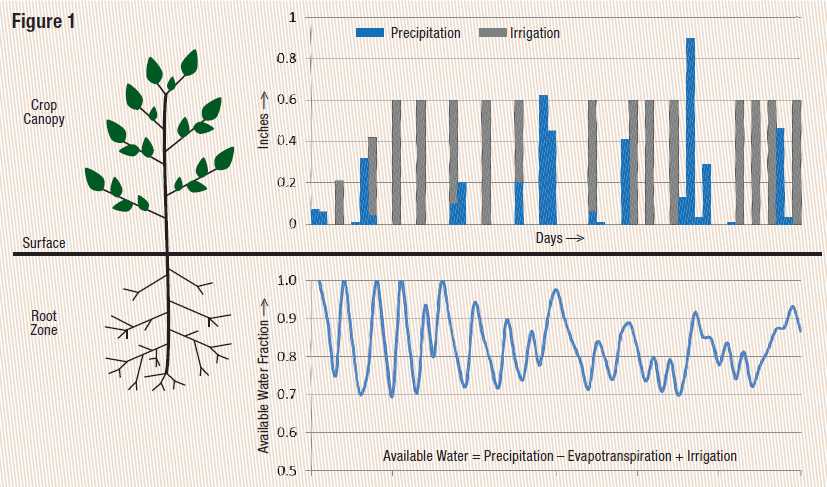

The graphical output of a simplified irrigation schedule using the water budget approach is shown in Figure 1.

It illustrates the interplay of precipitation, evapotranspiration and irrigation in the management of crop water requirements. As can be seen in the figure, the available water in a soil is the sum or budget of precipitation minus evapotranspiration plus irrigation. If a budget drops below a certain threshold due to the loss of water by evapotranspiration, then irrigation must be added to the soil. If there is precipitation, then irrigation can be reduced or withheld according to the budget.

The available water can be presented as a fraction of the maximum water stored in a soil. This fraction fluctuates daily as shown in the figure between a preset, crop-dependent, lower threshold of 0.7 and a maximum of 1.0 (field capacity) according to the precipitation, evapotranspiration and irrigation budget. An irrigation schedule begins just before planting and ends just before harvest. The amount of irrigated water is a function of soil texture and rooting depth, crop type, irrigation method and the capacity and efficiency of a system making applications. It is adjusted during a growing season based on root growth, crop stage and canopy size.

A schedule, as a water management tool, not only takes the guesswork out of the timing and amount of an application but also provides peace of mind because a grower knows that the water needs of a crop have been met. When coupled with soil sensors or imagery, a schedule can become a precision agricultural tool for prescribing variable rate irrigations.

The take-home message for this article is although we live on a planet with 71% of its surface covered with oceans, we must never lose sight that our local water sources can be limited and at risk for contamination. By understanding soil properties and crop water needs and employing the appropriate tools and practices, a grower can manage water resources intelligently and sustainably into the future.

WEBINAR ON DEMAND: Take the Challenge: Water Quality and Agriculture