The Ever-Evolving World of Ag Cooperatives

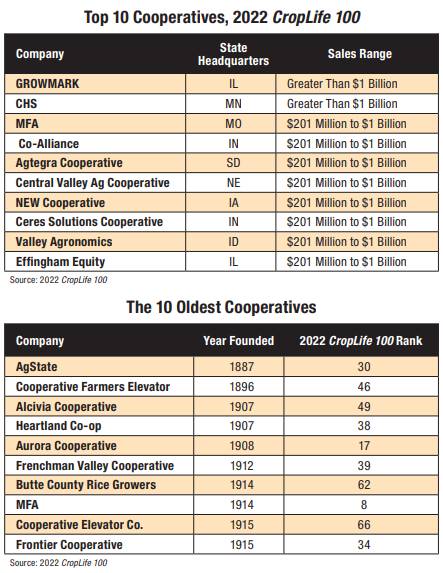

Looking back over the 40-year history of the CropLife 100, cooperatives have always played an important role in the annual rankings. Indeed, in the 2022 CropLife 100, 44 of the 100 ag retail organizations on the list were classified as cooperatives, with all but a handful of these topping $50 million in annual sales.

Looking back over the 40-year history of the CropLife 100, cooperatives have always played an important role in the annual rankings. Indeed, in the 2022 CropLife 100, 44 of the 100 ag retail organizations on the list were classified as cooperatives, with all but a handful of these topping $50 million in annual sales.

And in truth, what defines a cooperative in 2023 has not altered significantly from the definition the sector employed back in the early days of the 20th century — a farm business or other organization, which is owned and run jointly by its members, who share the profits and benefits.

But besides these basics, what it means to be a cooperative in 2023 has changed pretty significantly since the days when the CropLife 100 was new (back in 1984).

For example, in the 1980s, cooperatives tended to be smaller, local entities with just a few locations almost exclusively serving its member-owners. Today, cooperatives are multi-layered companies with diverse assets and offerings that cater to their member-owners and numerous other interested customers as well.

Related:

- CropLife 100 ‘Then and Now’ Photos: Here Are 22 of America’s Oldest Ag Retailers

- Southern States Cooperative at 100: A Story a Century in the Making

According to Wade Mittelstadt, COO at GROWMARK, Bloomington, IL, this “broadening of business scope” is a by-product of the times the agricultural industry lives in today. “Today’s agricultural business operates at a much quicker pace than it did 40 years ago,” says Mittelstadt.

Mark Orr, CEO at GROWMARK, agrees with this assessment. “Cooperatives have had to change with the times to continue to thrive,” says Orr. “To survive, they can’t remain static.”

In many ways, this view of cooperatives dates back to almost the start of the 21st century. For proof, consider this statement made in the early 2000s by then Executive Vice President/Sales & Marketing Dave Coppess at Heartland Co-op, West Des Moines, IA.

“This company is moving forward rapidly to adapt to the changes in the marketplace so we can continue to help our grower-customers grow and be more profitable,” said Coppess, speaking about the company’s merger with a neighboring cooperative. “If we as a company let ourselves get stagnant, we will die.”

Size Matters

In essence, one of the major differences between cooperatives in 2023 and 1984 is size. In the 1984 CropLife 100 rankings, the vast majority of cooperatives on the list had sales of less than $10 million, putting them as a group at the bottom of the list. On the 2022 CropLife 100 listing, however, 28 of the Top 50 ag retail organizations were cooperatives, averaging sales in the $150-million range. And two cooperatives — GROWMARK and CHS — recorded annual sales of more than $1 billion.

Part of how today’s cooperatives have managed to grow in size and business scope ties back to one of the hallmarks of the sector — consolidation. According to Marc Mears, COO at AgState, Cherokee, IA, this consolidation trend is not new. In fact, it dates back to the sector’s beginnings.

“Back in the early days, cooperatives were designed to bring economic value to their local membership,” says Mears, “and that is still the case today, just at a much larger scale.”

And the numbers back this up. According to statistics, the number of cooperatives in the U.S. has steadily declined since the early days of the CropLife 100. Back in 1990, there were an estimated 3,000 cooperatives spread out across the country. By 2020, this number had fallen by almost 75%, with approximately 750 cooperatives left.

“We’ve definitely seen this trend here in Iowa,” says Chris Behrens, Executive Vice President of Sales and Marketing at Heartland Co-op. “From around 200 cooperatives in the state at the start of the 1990s, we are down to 50 today.”

While mergers continue to shape much of today’s cooperatives marketplace, there is another newer trend beginning to take hold with many organizations — partnerships. For example, GROWMARK has developed numerous partnerships with other cooperatives in recent years, everything from co-managing grain assets to financially supporting technology innovators. In fact, the company has started a venture investments group in partnership with CHS to support this initiative.

“This is a big difference from the way we did business 40 years ago,” says Heather Thompson, Director of Innovation and the company’s liaison to Cooperative Ventures, the joint investment fund with CHS. “By investing in and partnering with some of the most promising startups in the ag tech space, we get the opportunity to be on the cutting edge of R&D while still maintaining our focus on wholesale and retail operations with excellence. It is a beautiful marriage of corporate and start-up working together. They have novel products and technologies, and we here at GROWMARK have the scale and channel relationships to help the innovative solutions come to life.”

The Speed of (Co-op) Life

Speaking of technology, this represents one of biggest changes for cooperatives in 2023 vs. cooperatives in 1984. “Back in the 1980s, custom applicators for cooperatives used to do everything manually, but they would get some breaks in the year to recover,” observes Lance Ruppert, Executive Director of Agronomy Marketing & Technology at GROWMARK. “Today, there are no more breaks like that — and that’s where technology can help.”

Monte Van Wyk, Director of Agronomy/Procurement at Heartland Co-op, agrees, pointing to differences in the grower-customer profile these days. “When I started in this business, the farms all tended to be 500 to 700 acres and all of the needs for those growers were pretty similar,” says Van Wyk. “Today, we still have those farms, but many more are in the 10,000-acre-plus range. That triggers very different decisions on our part regarding things like application and product mix.”

Monte Van Wyk, Director of Agronomy/Procurement at Heartland Co-op, agrees, pointing to differences in the grower-customer profile these days. “When I started in this business, the farms all tended to be 500 to 700 acres and all of the needs for those growers were pretty similar,” says Van Wyk. “Today, we still have those farms, but many more are in the 10,000-acre-plus range. That triggers very different decisions on our part regarding things like application and product mix.”

According to Dr. Jeff Bunting, Vice President, Crop Protection, at GROWMARK, this disparity in farm size has increased the need for technology among grower-customers. “Twenty years ago, yield monitors for farmers were more of an entertainment expense,” says Bunting. “But today, these units help them figure out the key differences in their crop fields — why this spot yielded 220 bushels vs. that one that only yielded 150 bushels?”

Bunting also says more modeling is being employed by cooperative grower-customers than ever before. “There’s a lot more scouting going on these days vs. 20 or 40 years ago to manage crop stresses,” he says. “And for many growers, this means using drones to inspect fields to compliment traditional scouting methods.”

GROWMARK’s Thompson agrees with Bunting. “I’ve seen a real shift in the market to embracing data to help everyone make decisions,” she says. “We’ve got so much information at our fingertips now vs. 40 years ago, and that can be really overwhelming. But over the past few years, we’ve seen the industry coalesce around how to leverage that data, make sense out of it, and drive that for insights. And I think we are right at the tipping point in how that data can help our crop specialists at the farmgate.”

Outside of technology, another area of a cooperatives’ operation that moves faster today than back in the 1980s is sourcing. In particular, this has impacted the crop nutrients part of the business.

“All of these things are changing much more rapidly today than 40 years ago,” says Mike Conover, Director of Agronomy Procurement for AgState. “There’s much more volatility now that affects our ability to get crop nutrients, especially recently.”

Of course, the recently he’s referring to is the ongoing Ukrainian-Russian War, now just past its one-year anniversary. Indeed, when asked to describe how running a cooperative in 2023 differs from in 1984, Kreg Ruhl, Vice President, Crop Nutrients, at GROWMARK uses a one-word descriptor — geopolitics.

“As I like to say, everything is shipping from the wrong place to the wrong place because of geopolitical instability,” says Ruhl. “For cooperatives like GROWMARK, this is driving up inefficiencies and costs across the system.”

According to Steve Becraft, CEO and General Manager at Southern States Cooperative, Richmond, VA, this geopolitical has radically altered how cooperatives manage their crop nutrients supply chain. “Unlike 40 years ago, we as a company can’t wait to order the fertilizer our customers need for three months,” says Becraft. “We’ve had to manage these market demands closer to the vest and do a lot more pre-planning than we ever used to have to.”

Executives at Moundridge, KS-based cooperative Mid Kansas Coop (MKC) also see challenges associated with geopolitics. “We need to understand the effects of geopolitical turbulence on our business and on our customers’ business and the impact on our supply chains,” says Erik Lange, EVP and COO.

Dave Spears, MKC’s EVP and CMO, adds that: “We are in a global marketplace, not only with regards to our outputs such as grain, but also the inputs we depend on from China and India and other foreign countries. It’s crucial to understand the geopolitical landscape, especially today, and we spend a lot of time focused on that.”

Safety First, Foremost

Another top priority for MKC is safety. A recent tour of the Safety Center in Moundridge illustrated just how dedicated the cooperative is towards nurturing a safety-minded culture and sharing its resources and commitment to safety with the broader ag community.

The Safety Center features a range of equipment and simulators that provide hands-on, interactive training and instruction, including a small-scale anhydrous ammonia tank, a spray table that demonstrates different spray patterns and drift issues, a grain engulfment simulator, and a mini grain elevator, among other working props.

There is also a semi-trailer brake station where participants can learn about air brakes, how they work, and how to set them to make sure they operate safely. Another station is devoted to the specifics of grain grading.

According to Spears and Lange, the Safety Center is in use most days. It’s an extremely valuable resource that MKC uses for meetings and internal training, as well as a teaching and demonstration facility for Future Farmers of America and 4-H students, fire departments and emergency rescue teams, and even other cooperatives in the region.

The Safety Center provides a range of benefits. For one, regulators tend to look at the “worst actors,” Spears points out. “They sometimes think everybody acts the same way. [However,] if we can raise the bar for everybody, then we raise the bar for the entire industry.”

There’s also a financial benefit. While it’s somewhat difficult to accurately assess how much lower insurance costs are as a result of the training acquired at the Safety Center, insurance companies recognize and reward its value.

“Telling the story of the Safety Center is one thing, but bringing [the insurance companies] in to see it for themselves makes rate negotiations so much easier,” says Spears.

Not surprisingly, the Safety Center has strong support throughout the MKC organization from the top down. MKC’s Jon Brown, Director of Facilities Management and Project Manager, and Scott Biel, Director of Safety, are continually evaluating the user experience and looking for ways to improve the Safety Center value proposition.

For the most part, new ideas and requests for additional simulators and equipment from Brown and Biel get the green light if it helps improve the safety of the organization, says Spears.

“If it’s a good idea and the benefit outweighs the cost then we consider it and typically move forward,” he says.

A Complexity Complex

Besides speed, cooperatives in 2023 are much more complex than they were 40 years ago. For instance, says Keith Lawson, Vice President, Seed, at GROWMARK, consider how much an average bag of seed has changed during this time. “A bag of seed in the 1980s would cost less than $100, and it was just conventional seed,” says Lawson. “Today, there is a lot of genetic technology that goes into that bag of seed and it cost several hundred dollars per bag. But the yield potential has improved substantially.”

In addition to expanding into new areas such as technology and input advances, many organizations also have branched out from their hometowns to have a much larger market footprint.

“Cooperatives are a far more sophisticated business than they were 40 years ago,” says Gary Halvorson, Executive Vice President, Enterprise Customer Development at CHS, Inver Grove Heights, MN. “Today, you have local cooperatives engaging in large technology investments and cutting-edge technologies at the cropping level. As agriculture continues to evolve, the cooperative system is actively innovating on behalf of its owners.”

Troy Upah, CEO at AgState, also has experienced this level of sophistication firsthand. In fact, his company was the result of a merger between CropLife 100 participants Ag Partners and First Cooperative Association back in September 2021. “As ag consolidation has lapsed, it has provided our cooperative’s leadership to get more specialized in our focus,” says Upah. “That kind of focus wasn’t necessarily available to cooperatives back in the 1980s, when everyone tended to be a ‘jack of all trades.’”

Of course, Upah points out that even with all the changes cooperatives have witnessed over the past four decades, their core mission to provide products and services to their grower-customers remains. “With all the digital transactions that take place today, you sometimes have to work really hard to keep in touch with the community you do business in,” he says. “But we will keep cultivating those relationships any way we can. And I don’t EVER see that aspect of our business changing!”