How Adjuvants Are Protecting Endangered Species

Fifty years ago, President Richard Nixon signed the Endangered Species Act (ESA) into law. The ESA is often called the “pit bull” of environmental law because of the broad authority and power it grants to regulatory agencies responsible for administering the Act.

The modern-day Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) was passed in 1972 — one year earlier than ESA passage. Congress established FIFRA and the accompanying Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) as the sole federal statutes for regulating pesticides. However, that’s not how non-governmental organizations (NGOs) saw it.

In 2001, ESA and FIFRA began to collide. That’s when NGOs used the much more expansive authority under the ESA to file suit against the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for its failure to “consult” with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) regarding the possible effects of 58 different pesticides on endangered salmon and trout in California, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. One of the key provisions of the ESA is the requirement that all federal agencies “consult” with either NMFS or FWS (collectively, “the Services”) if an agency action could affect threatened and endangered species.

That’s a problem because EPA and the Services have dramatically different views on how to assess and manage potential risks to fish, wildlife, and plant species from the use of pesticides. That’s because there are fundamental legal and science policy differences related to their respective obligations under ESA and FIFRA. The result has been an inability to develop a workable process for consultation under ESA. This conflict is now threatening agricultural productivity and global competitiveness while providing no corresponding benefit to threatened and endangered species.

Labeling Issues on the Horizon

Fast forward to today and after 20 years of legal wrangling following the filing of the first lawsuit and the filing of numerous “copycat” lawsuits, we are now at a point where ESA restrictions will appear on some FIFRA labels.

To drive home that point, two major ESA/FIFRA developments have occurred in the past few months. The first is the announcement of a settlement in the ESA “mega-suit.” This lawsuit was filed by NGOs in 2011 which sought to invalidate or severely restrict EPA’s registration of any pesticide containing one of 382 active ingredients because of EPA’s failure to consult with the Services. The settlement agreement narrowed the case to challenge a subset of products containing one or more of 35 active ingredients.

The second is the release by EPA on July 24 of its draft “Herbicide Strategy,” which EPA describes as “a major milestone in the Agency’s work to protect federally endangered and threatened (listed) species from conventional agricultural herbicides.” The Strategy outlines proposed mitigations “for more than 900 listed species and designated critical habitats to reduce potential impacts from the agricultural use of these herbicides while helping to ensure the continued availability of these important pesticide tools.”

This leaves agriculture in a bad spot because pesticide registration and registration review are now regulated by a hybrid between FIFRA and ESA. To that point, before EPA registers any new conventional active ingredient, they must conduct an ESA assessment to determine potential effects to threatened or endangered species. If a product could cause “jeopardy or adverse modification,” EPA must add mitigation measures to the label before they can issue the registration. This new hybrid model also applies for products going through registration review.

Adjuvants Aid

This is where adjuvants enter the picture. There are a variety of potential mitigation measures designed to address new label restrictions. The goal is to reduce spray drift, surface water run-off, and pesticide transport through erosion by implementing “no-spray” buffers near species habitat.

For a pesticide with an ESA 150-foot no-spray buffer, a grower or applicator would have four options. First, select an alternative product that does not have a buffer. For some pests and situations, that might not be possible. Second, leave that portion of the field untreated. Third, do not plant or farm that part of the field. Fourth, add a drift reduction adjuvant tool to the mixture to either reduce or eliminate the buffer or to use another mitigation option, such as a hooded sprayer.

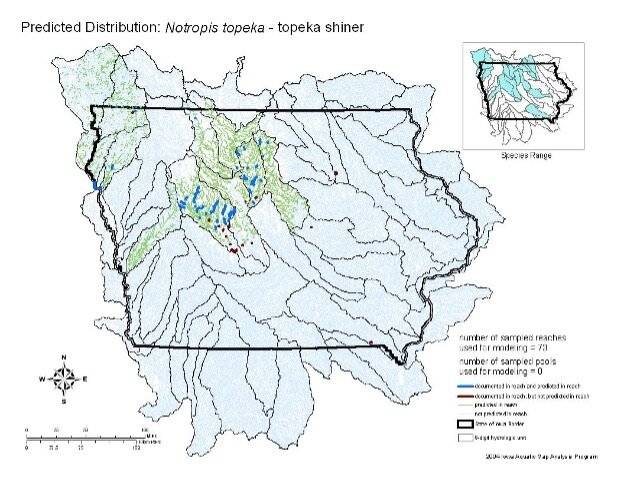

To illustrate the potential effects to agriculture of these restrictions, pictured here is a map from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources that shows the Iowa species range for the Topeka Shiner — a small fish listed under the ESA. To be clear, not all these areas will face no-spray buffers. In fact, some areas will face little in the way of restrictions or impact. However, farmland adjacent to streams, wetlands, rivers, and intermittent waterways that feed lakes and water bodies where the Topeka Shiner exist, could.

In this example, without the adjuvant option, the effects to agriculture and others who rely on crop protection products could be devastating, especially for growers who are farming small acre fields near protected waterways and species habitat. For example, a 10-acre field with a no-spray buffer could mean the loss of half the field or more unless the grower uses an adjuvant. For other growers, the economic impact can’t be ignored as a 10-acre no-spray buffer on a 100-acre field means a potential 10% drop in revenue.

To address this, the Council of Producers and Distributors of Agrotechnology (CPDA) is working with EPA and CropLife America on including adjuvant data into CropLife America’s Mitigation Strategy Tool or MiST. CropLife America and Compliance Services International (CSI) developed MiST as a centralized location for pesticide mitigation resources, historic evaluations of mitigation practices, and best management practices designed to protect species. CPDA is collaborating with its member companies on compiling adjuvant drift reduction data so that it can be included in MiST and relied upon as an effective and economical mitigation tool. At this point, EPA has not included the adjuvant option in any of their mitigation solutions.

Congressional Aid

To leave no stone unturned, CPDA is also working with Congress and USDA. Adjuvants are already a part of the USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service’s (NRCS) 595 Practice Standards as a means of reducing offsite movement. CPDA is working with USDA to make that a more prominent feature and benefit to make farmers, working with their local NRCS office, more aware of this option.

Separately, we are supporting Farm Bill provisions to re-energize USDA Centers of Excellence to prioritize and include an adjuvant component in its research and outreach, so growers have the latest benefit information on utilizing adjuvants in their precision agriculture activities.

An important point that is almost always overlooked is simply this. The use of pesticides and adjuvants benefits endangered and threatened species by conserving critical habitat. Conservation scientists rank habitat destruction and invasive species as the two most serious threats to endangered species. The use of pesticides and adjuvants protects endangered species in two ways. First, pesticides increase crop yields. This reduces the amount of land needed to produce food, enabling marginal lands to be kept out of production and freeing more land for conservation and to preserve critical habitat. Second, pesticides increase the diversity and quality of natural habitat through the control of non-native or invasive species that damage our waters, farms, and natural areas.

Pesticide application stewardship and training are a continued need within agriculture. Not only do adjuvants help growers make more efficacious and on-target applications, but they are also a key piece of the ESA puzzle.