Gulf Hypoxia Battle Still In Early Rounds

It took decades for the hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico to develop. It’s going to take decades to wipe out. That’s the most recent conclusion not only of a February 2015 EPA report but of the many groups that have been developing and implementing strategies to prevent nutrient losses.

Several states in particular have been hard at work, but they’re far from meeting the goal the agency’s Hypoxia Task Force set in 2008: Cut nitrogen and phosphorus loads to the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin (MARB) by 45% by 2015. So, in February EPA revised the goal downward, aiming instead for a 20% reduction in loads by 2025.

Another goal was to shrink the Gulf dead zone to about 2,000 square miles by 2015. It hasn’t happened. In fact, in spite of stakeholder efforts, scientists are seeing that the average five-year size of the dead zone has remained largely unchanged since 1994 — almost 6,000 square miles, an area about the size of Connecticut. The deadline to meet this goal also been pushed out, to 2035.

The rethinking of expectations is not surprising, considering the sheer size and diversity of the MARB, where waterways spanning 31 states and two Canadian provinces ultimately drain into the Gulf of Mexico.

Responsibility & Accountability

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has determined that agricultural sources actually contribute more than 70% of the nutrients that enter the Gulf. Hence, in 2008 the 12 states along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers — which contribute water to the Gulf — were specifically charged with developing their own nutrient reduction strategies to lower nitrogen and phosphorus releases.

All 12 states (Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Illinois, Missouri, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee) have now written their plans, at least at the draft stage. CropLife® has reported on water protection efforts in three particularly proactive states — Ohio, Iowa and Illinois — in previous stories in the Water Watch series.

Funding & Focus

One state that’s been a leader in nutrient management efforts is Mississippi. Perhaps with good reason. In 2008, when USGS drew up the list of the leading watersheds contributing to nutrient loads in Gulf, the Delta region in northwest Mississippi — ground zero for row crop production in the state — was on it. “That got the attention of the governor’s office,” says Richard Ingram, who is currently associate director of Mississippi State University’s Water Resources Research Institute and director of Mississippi’s Center of Excellence for Watershed Management.

Then, too, state officials felt it was time to move on water problems because hypoxia had actually been detected off Mississippi’s coast by University of Southern Mississippi researchers, in the Mississippi Sound. “We were in the midst of a very challenging experience complying with a federal consent decree for the development of Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs), an issue that affected over 40 other states, and felt that we should do all we could to avoid a similar situation with nutrients,” says Ingram. “So we moved ahead and started taking care of our own problems.” His feelings reflect those felt by many trying to keep up with government mandates on water controversies.

Ingram has a long history on the Gulf hypoxia issue and has been deeply involved with the Hypoxia Task Force which was formed in the late 1990s. “While the group recognized the challenges in the Gulf, its early efforts really didn’t gain traction in the states because of the lack of funding,” he says.

Fortunately, since 2008, monies have become available through a wide array of federal, state, and NGO programs. The funds are greatly needed because the issues fueling Gulf hypoxia are so complex. In his 20-some years with the Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality and on the Hypoxia Task Force, Ingram has worked to heighten the focus on nutrient reduction efforts. Mississippi’s strategies were developed to answer three key questions: What nutrient reductions are achievable and when; what are the costs; and what are the benefits.

One issue Ingram has helped address is how participants measure progress. Mississippi’s nutrient loss reduction strategies — which have been shared with other states — include the concept of tiered monitoring: Analysts start by monitoring fields, then move to catchments, then on to a watershed scale.

“In the first 12 to 18 months you see improvements in water quality at the edge of the fields. We’re finding it’s taking years to start seeing those improvements at the catchment scale,” Ingram says. “You can imagine the extrapolation needed all the way to the Gulf. It’s going to be a generational issue.”

Early on, Ingram says his team wanted to not only lead Mississippi’s nutrient work but to try and influence what was going on upstream within the watershed. They entered into a strategic partnership with Iowa. One of the most visible events orchestrated by the pairing came in 2011, a Farmer-to-Farmer Exchange. In the exchange, growers and other stakeholders from Iowa and Mississippi visited each other’s states, touring farms and viewing nutrient reduction projects. A notable guest on the tours was Iowa Secretary of Agriculture Bill Northey, who attracted crowds and media at each stop.

The biggest ag stakeholder group in the Mississippi Delta, Delta F.A.R.M. (Farmers Advocating Resource Management) helped with the exchange — and was a co-lead in developing the state’s nutrient strategies This association, which consists of growers and landowners, “strives to implement recognized ag practices which will conserve, restore, and enhance the environment” there. This powerful ally in the Mississippi’s nutrient work also helps generate funding and secure expertise for projects.

Dealers’ Help

Dealer/distributor Pinnacle Agriculture Distribution, Inc., based in Memphis, TN, has worked closely with Delta F.A.R.M. The company has a huge presence in the southern states that impact the Gulf. Its original footprint includes Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee and Arkansas, though the firm has been expanding throughout the U.S.

Chism Craig, vice president of research and development, says protection of the Gulf is important to the Pinnacle, but it doesn’t necessarily drive day-to-day operations. The reason? “We feel we were there before it became a big issue,” he says. His company has long been conservation-focused, with programs and practices already in place to help steward nutrients.

“If we’re implementing the 4Rs, then we’re doing our part not only for conservation, but we’re giving our farmers a return on their investments,” Craig points out.

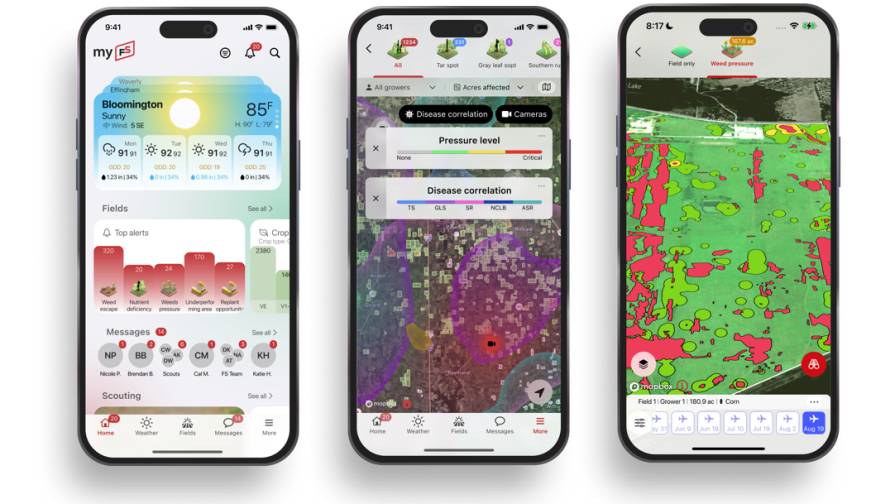

A big part of Pinnacle’s approach is its proprietary precision ag program, OptiGro. As part of that service, the company soil samples nearly half a million acres every year and variable-rate applies needed nutrients.

In the last few years, Pinnacle has made cover crops a bigger part of its management recommendations. The firm carries a wide range of varieties, including custom blends to fit specific field situations. Options available can include radishes, rye, triticale, Austrian winter peas, and vetch. One cover crop may be really good for corn, but not the best for soybeans, Craig says.

Pinnacle’s growers have seen “a huge benefit,” especially during this past season’s early wet weather, with nitrogen stabilizers. They not only prevented N from being lost, they kept the nutrient available for crops to use.

Craig says that while Pinnacle does not focus on measuring losses, his staff “listens to the people who have done that and incorporates the practices they’ve discovered that reduce nutrients leaving the field.”