What’s Next With Glyphosate? Top Ag Retailers Weigh in on Roundup

While most of agriculture in 2019 was engaged in playing a form of survivor, perhaps the ultimate example of this kind of reality game taking place involved glyphosate. To say it’s been a rough year for the popular herbicide would be a gross understatement.

Before looking at the present situation for glyphosate, a glance backward is probably in order. Since it first appeared in the world’s crop fields in 1974, glyphosate has been often hailed by many agricultural watchers as “a 100-year molecule.” Effective against both broadleaf weeds and grasses, glyphosate quickly became the agriculture’s industry most popular herbicide for grower-customers to control stubborn weeds in their crop fields. Furthermore, with the introduction of glyphosate-resistant Roundup Ready crops in the mid-1990s, the popularity of the herbicide increased ten-fold. In the end, usage of glyphosate even expanded into the consumer sector through several products sporting the Roundup name on their labels.

Through it all, of course, the herbicide became one of the most researched agricultural active ingredients in history — a point made by Bob Reiter, Global Head of Research and Development, Crop Science Division for Bayer. “Glyphosate is one of the most studied molecules that has ever been introduced into the agricultural marketplace,” Reiter said, speaking at a fall 2018 Bayer event. “Time and time again it’s been shown to have a tremendous safety record.”

Ultimately, having its safety being backed by this small mountain of scientific research was what led Bayer to decide to acquire glyphosate’s original producer, Monsanto, in 2016 (with the deal finally closing in 2018). This created a huge crop protection products/seed giant in the ag industry, with annual global sales in the $22 billion range.

Lawsuits a Plenty

Unfortunately, about the same time Bayer was bidding to purchase Monsanto and its assets, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) released a report that looked at the safety of glyphosate. Using only data from certain studies on the herbicide (and rejecting the opinions of many of the world’s foremost regulatory agencies, including EPA’s), IARC’s report concluded that glyphosate was a “probable carcinogenic.”

About the same time this report was being published, several consumers who had used glyphosate around their homes or as part of their jobs began filing lawsuits against Monsanto. Most of these claimed that long-term exposure to glyphosate had caused the plaintiffs to develop a form of cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

About the same time this report was being published, several consumers who had used glyphosate around their homes or as part of their jobs began filing lawsuits against Monsanto. Most of these claimed that long-term exposure to glyphosate had caused the plaintiffs to develop a form of cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

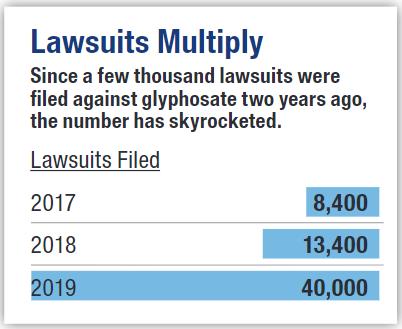

As the first of these lawsuits began going to trial in California, many observers weren’t sure what to expect. However, the news was overwhelmingly negative for glyphosate and Bayer: $289 million in damages against the company in the first, $1 billion in damages in the second. Although both judgments were later reduced, the floodgates were now open. Legal firms began a nationwide campaign asking for anyone who believed they had developed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma from using glyphosate to come forward. Ultimately, the number of lawsuits against Bayer and glyphosate swelled from “a few thousand” to an estimated 40,000 by the end of 2019.

Besides the lawsuits, many countries around the world have now banned glyphosate use within their borders based on the IARC report and U.S. courtroom verdicts against the herbicide. Going into 2020, this list includes Vietnam, Austria, and Bayer’s home market of Germany (although this ban won’t go into full effect until 2023).

CropLife 100 Views

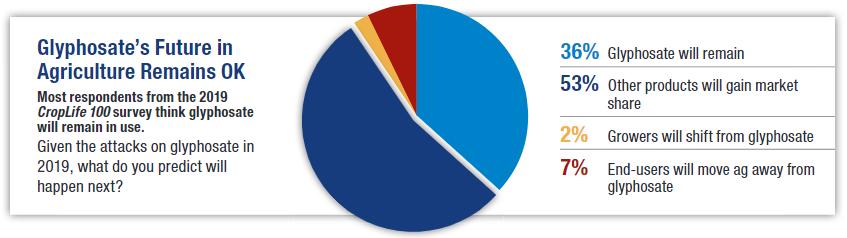

Based on these developments regarding glyphosate over the past year or so, CropLife® magazine decided to ask the following question to the nation’s top ag retailers on this year’s CropLife 100 form: “Given the attacks on glyphosate in 2019, what do you predict will happen next?”

The smallest percentage (2%) of respondents believe that grower-customers would begin to shift their herbicide needs away from glyphosate during the 2020 growing season. A slightly higher percentage (7%) expressed the view that end-users and the processors who supply them products would “dictate” the grower community begin moving away from using glyphosate on their crops in order to promote them as “glyphosate free” to consumers.

This harkens back to something observed about glyphosate one year ago at the Future of Farming Dialogue event in Germany. “This is a political molecule,” said Bill Reeves, Regulatory Policy and Scientific Affairs Manager for Bayer. “It’s become a way to drive concerns among consumers about genetically modified organism use.”

Still, the largest percentage of 2019 CropLife 100 survey responders (53%) believe that their grower-customers will begin using other herbicide products to satisfy those end-users that wanted crops grown without glyphosate use (such as planting traditional-bred seeds or utilizing other herbicide-resistant cropping systems, such as glufosinate, 2,4-D, or dicamba).

Of course, in the end the remaining 36% of CropLife 100 ag retailers think that glyphosate will remain an important tool for agriculture to use “for years to come.” Part of this is probably based on the fact that the vast majority of lawsuits filed against the herbicide come from the consumer sector and not agriculture.

And others may be putting their faith in Bayer (and eventually the rest of the crop protection products community) to fight to keep glyphosate as a tool to fight yield-robbing weeds. “Monsanto at some point more or less gave up trying to educate the population on glyphosate’s safety,” Liam Condon, President of the Crop Science Division for Bayer, said one year ago at a press briefing on glyphosate’s future. “We have to try to do this going forward.”