Crop Protection Rebates: Playing the Game

From the earliest days of competitive selling, the concept of rewarding customer loyalty has been a page, if not a full chapter, in the capitalist playbook. Rewards set aside for customers that purchase set amounts of product over a given period of time is as American as apple pie.

Crop protection products in ag are certainly no exception. Manufacturer-generated customer loyalty programs emerged in the late 1970s and 1980s, when new active ingredients and product formulations were being churned out annually and competition for shelf space was extremely fierce. Over the three decades since, much has changed — but the loyalty programs, which distributors and retailers receive in the form of rebates, remain.

That said, how the rebate concept itself has evolved is a point of contention and frustration for many in the distribution channel. Factors such as industry consolidation and the rise of “price transparency” through the efforts of organizations like Farmers Business Network (FBN) has deepened the issues many retailers and distributors have with the current system.

Truth be told, while manufacturers have tried to create a system of loyalty programs that sell product and create equity in the market, wickedly competitive retailers and distributors have always found a way to take full advantage of backroads and loopholes in the programs, from the earliest days to today. But market forces are raising the stakes, stripping bigger chunks of profit out of the crop protection value chain and putting tremendous pressure on distributors and dealers.

While many retailers expressed an interest in sharing thoughts, few wished to have themselves quoted for this article. This analysis combines the comments of experts and retailers on the front lines of the rebate issue.

In The Beginning

From the standpoint of research and development companies, the crop protection industry of 30 years ago — with a dozen or so large basics cranking out new chemistries and formulations at relative breakneck speed — is almost unfathomable today as the industry watches consolidation reduce the basics by two more companies in the ranks.

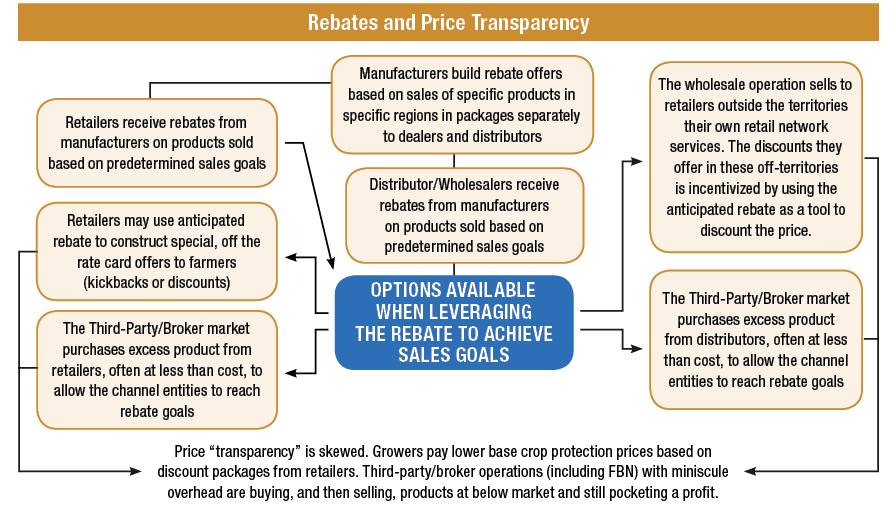

Loyalty programs rose out of the cacophony of hyper-competitiveness in the late 1970s and 1980s, and many started as controlled margin programs. Controlled by the manufacturer, distribution was not allowed to sell fair-trade products at below fair-trade prices. Even geography was controlled, as distributors could only sell in specific, designated geographies. One particular practice — providing rebate opportunities to both retailers and distributors separately — has proven particularly problematic in recent years. More on that in a little while.

The restrictiveness of the programs eventually attracted regulatory attention, and manufacturers had to drop many of the restrictions they placed on distribution starting in the 1990s. They had to find another way to reward loyalty, which would birth the concept of loyalty-based rebates.

Early on, the programs were not very transparent and loyalty earnings were often unpredictable, notes one retailer. “Rebates began as a point of differentiation when they were first launched as ‘black boxes,’ and nobody knew how to estimate or calculate them,” he explains. “They were just a nice surprise at the end of the year. And it delighted the retailer so they did more business with them the following year.”

Eventually the rebate programs became more transparent, with marketing packages that specified clear rebate percentages that were achievable under precise sales circumstances. Often, the rebate was tiered and the rebate percentage increased with increasing sales volume.

With transparency came major challenges for the retailer — and opportunities. With a known sales goal, a known percentage of rebate, and no specific penalty for distribution-wholesale organizations who choose to sell outside their traditional region, the room for business hijinks increased.

“Today, rebates represent a huge part of our revenue stream in the agronomy segment,” he says. “We analyze all the programs and try to estimate what that bottom line number is going to be,” so decisions can be made about pricing. These decisions, made by distribution and retail organizations separately based on their individual rebate programs, necessarily altered the view of rebates from “end-of-year bonus” to “built-in profit assurance.” Looking at sales goals and rebate potential holistically, rebates can be bolted onto the total profit picture. Decisions about buying and selling products, product pricing, and to whom products are sold, include rebate dollars in the accounting from start to finish.

Where It Gets Ugly

Understanding the full crop protection picture — cost of product, and how much product must be sold to achieve the full rebate is, on its face, a powerful planning tool. Clever retailers and distributors can use this information to ratchet down prices while maintaining an acceptable level of profit.

But the maneuvers don’t end there, in particular in difficult times. Retailers can use the rebate as a discretionary incentive tool to pass on to growers who commit to buying targeted products, essentially using the rebate to achieve sales that will drive the rebate payment for the retailer.

Distributors who wholesale to retailers, brokers, and other third parties in regions outside the territories covered by their retail network can use the rebate to incentivize product sales in those outside regions when additional product sales are required to achieve a full rebate. By factoring in the rebate, a distributor could sell a product to a third party at below the product cost, providing the third party a quasi-rebate if they, in turn, sell the product at or slightly above cost.

None of these maneuvers are new, but the additional pressure of price transparency driven by third-party crop protection resellers like FBN makes these sorts of transactions self-defeating for the distribution channel.

FBN has been gathering and sharing sales data from growers who are procuring product with wild and seemingly nonsensical price variations across geographies for common, popular crop protection products. In some cases the reporting is likely faulty, but in many others the low prices can be traced back to legitimate transactions from the distribution channel to FBN and third parties like them.

How much of this is going on is anybody’s guess. Off the record, retailers express a number of different theories and point fingers at specific players in distribution, but with not much proof and never on the record.

Here To Stay?

Talk about rebates with distribution channel entities and you hear words like “necessary evil” and a “terrible system, but we’re stuck with it.” Experts we spoke with feel that rebates are going to be with us for some time to come, as basic research companies try to maintain market share of a dwindling portfolio of proprietary products. That said, consolidation and a reduction in the number of players in the game could finally serve to bring some sanity to how rebates are constructed.

Syngenta and Bayer each made a concerted effort to cut rebates in recent history, only to get destroyed in the market, forcing a retrenchment and reinstatement of loyalty programs. And since collusion is illegal, it would take one bold organization with a full-on commitment to change the system, and stick with it long enough to have the others follow. Stay tuned …