California Water Saga Takes A Turn

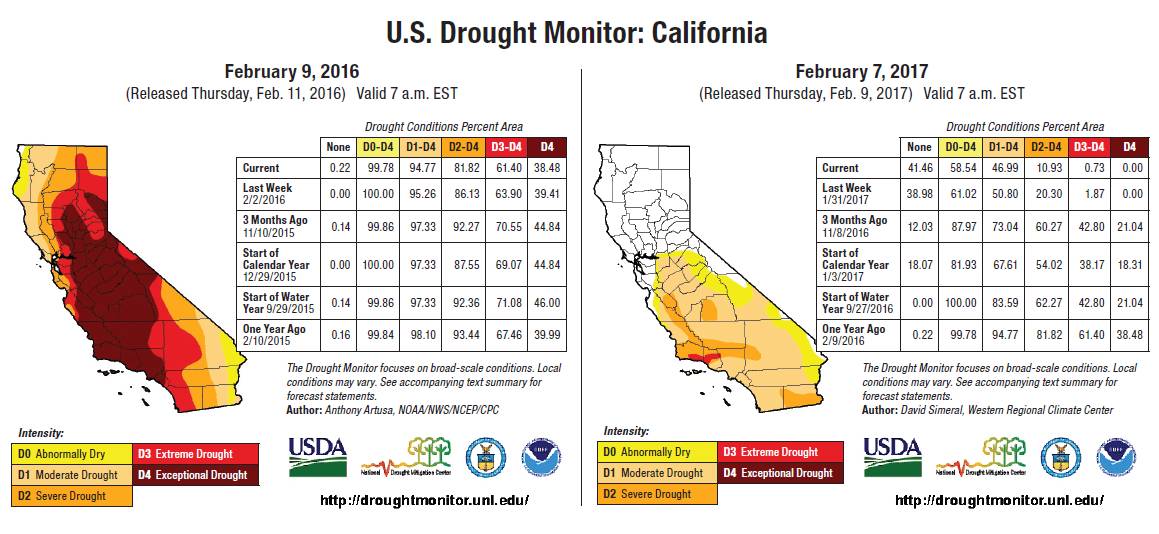

Stunning rain and snowfall in California have been making national headlines over the last few months. Initial reaction would be to rejoice that the state’s five-year drought is over.

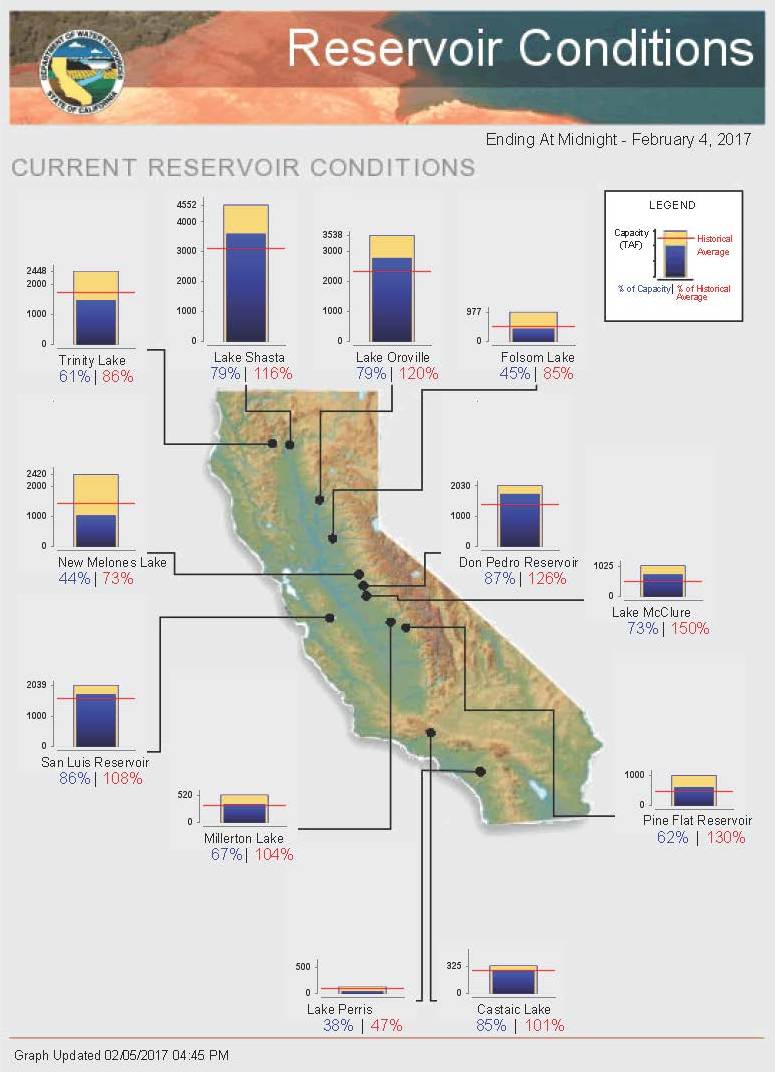

“I think everyone is very, very, very encouraged with this year’s rainfall. The rivers are full and running, we’ve opened our bypasses,” says Peter Bostrom, section chief with the California Department of Water Resources (DWR). Major reservoirs throughout the state are close to or above the average historical storage levels.

But due to recent trouble with two spillways at the Oroville Dam north of Sacramento, more than 200,000 residents had to evacuate their homes. There was concern over how the system would hold up through the next series of storms, which moved through after Valentine’s Day.

[Related: Technology Vital In California Water Management]

Snowpack in the Northern Sierra is at 151% of normal average for the same period, the Central Sierra is at 181%, and the Southern Sierra is at 206%. “From snowpack we can infer a very good year of surface water supply, says Daniele Zaccaria, agricultural water management specialist with the University of California, Davis. In normal years, the Sierra Nevada snow melts slowly in spring and early summer, supplying reservoirs and the whole surface water system in the northern half of the state. Water is then moved to the southern part of the state through federal and state water projects.

Unfortunately, “it would just take some really warm storms to melt it very quickly,” points out Michael Cahn, water resources and irrigation advisor with the University of California Extension in Salinas. “The water could hit those reservoirs which are already filling up.”

Officials are trying to track potential snowmelt problems. At some reservoirs where the current levels are below average, they’re keeping space available for flood prevention and mitigation — a common practice in reservoir management.

The excessive rain has caused a measure of uneasiness as well. “We’re getting close to where we may be concerned about too much water,” admits Bostrom.

In contrast, while the northern half of the state is looking good, its central and southern portions — harder hit by the drought — are still struggling. Their water supply comes solely from rainfall. At presstime on the Central Coast, one key reservoir was 80% full — at the height of the drought it had fallen to 30%; another has reached 28% of capacity, up from a low of 6%.

There should be much less groundwater pumping over the summer which will allow levels to rebound somewhat, says Bostrom. “But it will take a long time to come back from as deep as we’ve pumped some of these aquifers,” he adds.

Indeed, recent high precipitation will help replenish some water in aquifers, but most in the Central Valley are actually in a state of chronic overdrafting, a practice that’s putting into question the economic viability and environmental sustainability of irrigated agriculture in California, says Zaccaria.

Governments’ Role

No matter the weather, two other huge issues in the state remain: a troubled infrastructure and chronic disputes over who gets the resource.

Congress, which has intervened in the past on California’s water problems, stepped in again in late 2016. It passed a wide-ranging bill that authorized water projects across the country, including more than $500 million to provide relief to the state.

The Water Resources Development Act of 2016 will give water managers much needed operational flexibility to expedite water transfers, update the science being used to make valuable water flow decisions and authorize much needed funding to expand water storage throughout California, explains George Radanovich, president of the California Fresh Fruit Association.

But it is only an important first step toward restoring California’s outdated water system, says Tom Nassif, Western Growers Association (WGA) president and CEO. It is vital that winter rains “be judiciously diverted to storage.”

In late 2016, Congress also passed the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act (WIIN). Among its provisions, the WIIN Act allows water agencies to capture more water during winter storms and requires them to maximize supplies consistent with law. This winter will be a good test of how agencies adhere to that law, said Paul Wenger, president of the California Farm Bureau Federation.

The WIIN Act also funds California water storage and desalination projects, complementing the investments the state’s voters made when they passed the Proposition 1 water bond in 2014.

“We’ve had to let too much water run out to sea this winter, because we didn’t have any place to store it,” said Bill Diedrich, president of the California Farm Water Coalition. “We should be doing everything we can to save today’s rain and snow for use tomorrow.”

The California Water Commission will decide later this year on water projects to be funded through the bond.

The California Water Commission will decide later this year on water projects to be funded through the bond.

“You would think that a snowpack in the range of 179% of average would assure plentiful water supplies, but that link was severed long ago,” said WGA’s Nassif.

California’s water system is astonishingly complex. Decisions on use can be made on the federal, state or local level — though DWR’s Bostrom says much of the water infrastructure is controlled locally, through more than 200 irrigation districts.

The condition of those structures varies widely. Some are “great,” he notes, some are older. Stakeholders are tapping into a water delivery system made up of 100 year old reservoirs, canals and leveled farm ground all paid for by water users decades ago.

Uncertainty remains as to what 2017 — and the years ahead — might hold for precipitation in California. There’s no guarantee the storm systems experienced through the first half of the state’s rainy season will continue. Climatologists have called the weather patterns unpredictable at best. One water expert with Metropolitan Water District of Southern California says 2017 could stand as a single wet year followed by more dry years, as was the case in 2011.