Ag Retail Consolidation: What’s Continuing to Push the Trend?

On September 1, following many months of planning, Agland Co-op, New Philadelphia, OH, and Heritage Cooperative, West Mansfield, OH, completed their proposed merger. The move brought together more than 30 cooperative locations serving 3,300 grower-members in a 20-county area of Central Ohio.

In a joint released statement, Agland President/CEO Jeff Ostentoski and Heritage President/CEO Eric Parthemore had this to say about the consolidation: “The merger of Agland Co-op and Heritage Cooperative will create a dynamic organization built for the future. It will be a cooperative that brings value and benefits to members, employees, and our communities while protecting members’ equity, without compromising our fundamental core values and social responsibilities.”

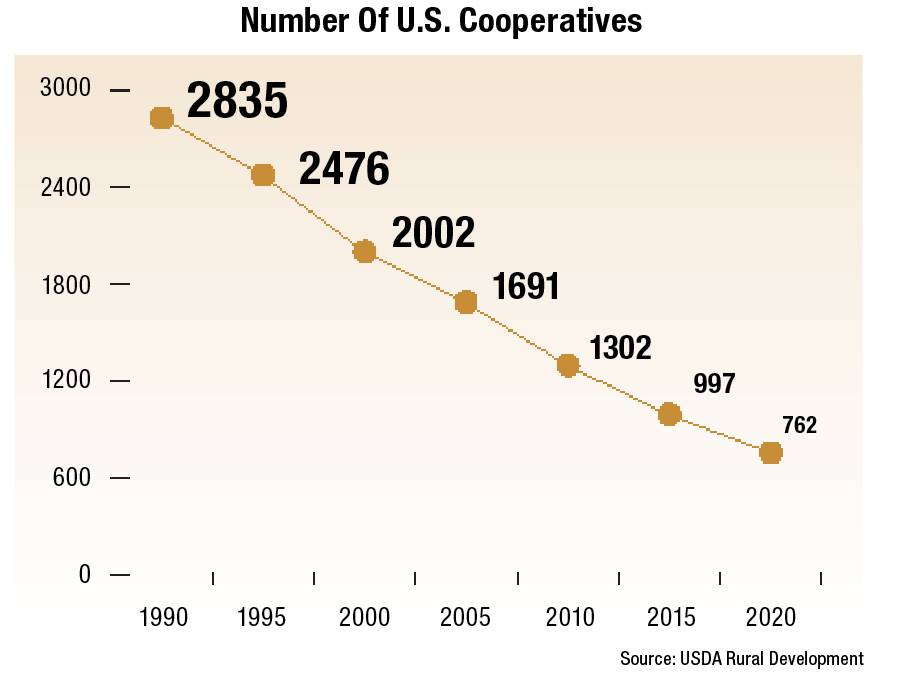

And with that, what was once two cooperatives is now one, continuing an overriding trend in today’s agricultural marketplace, rapid consolidation at the ag retail level — kept moving forward. Unlike in any time during the past 20 years, say market observers, farm cooperatives are under increasing pressure from multiple factors, including global competition. This is forcing many of them to make hard choices, including formally merging their operations with one-time marketplace rivals. In fact, according to USDA statistics, the number of cooperatives within the U.S. has fallen from just over 6,500 back in the mid-1970s to less than 1,000 today (see graph below) due in large part to the consolidation trend.

Pressure from All Directions

And this shows no signs of slowing down. In fact, even cooperatives that have failed in their consolidation attempts keep trying. For example, members for Wheat Growers, Aberdeen, SD, and North Central Farmers Elevator (NCFE), Ipswich, SD, originally voted down a proposed merger of the two companies back in 2016. In many cases, this would have been the end of any such talk.

However, in mid-August, the two board of directors for both companies once again decided to put forth a membership vote for a formal merger of Wheat Growers and NCFE. “The value to our members is what’s driving the decision by the boards to move forward with the effort to unify the two cooperatives,” said NCFE Board President Rick Osterday of this second round of voting. “Members have told us that unification will help us be better able to compete at a time when we see lots of competitor growth in the region.”

In many cases, the competition being faced by cooperatives is coming from large agricultural corporations. Traditionally, cooperatives primarily served as places where growers bought grain and stored it until it was shipped out to end-users. Now, however, many larger farms own their own grain storage and/or sell grain directly to large ag giants such as Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) and Cargill. In many cases, says Dave Coppess, Executive Vice President of Sales and Marketing for Heartland Co-op, West Des Moines, IA, this has forced cooperatives to “branch out” into a number of capital intensive technical areas such as precision agriculture to maintain their market edge.

“For many of our members, I compare today’s cooperatives to big old oak trees, with lots of older branches such as grain to newer ones such as precision agriculture,” says Coppess. “And of course, it costs money to keep all of these branches in perfect health. But when the flow of money gets smaller, as we’ve seen happen in agriculture during the past few seasons, many cooperative trees are being forced to think about which branches they might have to cut off, the big old ones or the new little ones, to keep the whole tree alive. So in many cases, the best solution seems to be to combine two trees into one.”

According to most market observers, this situation for today’s cooperatives is a direct result of today’s overall agricultural economy. Not too many years ago, between 2009 and 2013, commodity prices were at all-time highs, with corn selling for more than $8 per bushel and soybeans topping the $16 per bushel mark. Since the start of 2014, however, these prices have dropped back to their traditional marks, just over $3 per bushel for corn and $8 per bushel for soybeans, so grower-customers are pinching every penny they have when it comes to spending money at their neighborhood cooperative.

In fact, this “economic downturn” in agriculture is the reason Greenville Cooperative, Greenville, WI, decided to merge its operations with United Cooperative, Beaver Dam, WI, back in April of this year. “Changes in both the economy and agriculture had put increased demands on our cooperative’s efforts to provide needed products, services, expertise, facilities, and equipment for members’ growing needs,” said Greenville Cooperative’s General Manager Mark Schleiss, announcing the merger in March. “Being part of United Cooperative will give our members greater financial strength for their investment.”

This sharing of resources also motivated another set of cooperatives to combine their operations recently. On September 1, Ceres Solutions, Crawsfordville, IN, and North Central Cooperative, Wabash, IN, formally merged. The newly combined company features 60 outlets in more 30 counties spread out across Indiana and parts of Michigan. “Our two companies decided it made good financial sense for our cooperatives to merge,” says Jeff Nagel, Agronomist for Ceres Solutions. “This way, we can build upon the existing strengths we already had in our markets while tapping into additional resources to grow our businesses.”

Another such merger of cooperatives also took place on September 1, when Danvers Farmers Elevator, Danvers, IL, combined with United Prairie LLC, Tolono, IL. “We believe this merger will provide additional benefits and services over a broader geography to all our patrons,” said Danvers Farmers Elevator General Manager Steve Feeney, of the move. “Coming together allows us to combine resources to help our growers optimize their yields season after season.”

Roger Miller, United Prairie Board Chairman, echoed this sentiment. “We expect this move will provide improved leverage and access to resources for the supply of inputs, cutting-edge technology, enhanced market knowledge, and expertise in the ever-changing marketplace for farm input resources,” said Miller.

Of course, some of the recent cooperative have been about resources (i.e., money) on a more basic level — as in they had none available to them. In fact, according to George Secor, President/CEO of Sunrise Cooperative, Fremont, OH, this is what he had to deal with during his first tenure as CEO.

“A lot of cooperatives in the past year that merged had no other choice than to do so because they were in some bad financial straits and didn’t really have any other alternatives to stay in business,” said Secor during a spring 2017 interview with CropLife® magazine. “I know a little about this kind of scenario first-hand. When I first became CEO of this company, when it was called Country Spring Farmers Co-op in 1996, it was a merger of three cooperatives called RuralServ, River Springs, and Bellevue Farmers. Those cooperatives all had bad bottom lines and financial challenges that took our management team almost three years to dig out from under.”

However, this wasn’t the situation Secor was dealing with when Sunrise Cooperative embarked on its most recent merger, combining operations with Trupointe Cooperative, Piqua, OH. This merger, which completed on September 1, 2016, was about remaining relevant in a rapidly changing agricultural marketplace. “That’s the one word I kept using as Sunrise and Trupointe held some 35 merger meetings throughout the two companies during January and February of 2016,” he said. “We were both coming off really strong financial years. At the same time, I kept telling our board that with what was going on across the agricultural space, the decks could easily get re-shuffled and we could suffer as a company. In fact, I reminded them that 10 years ago, Sunrise and Trupointe each would have easily ranked in the Top 10 cooperatives in the country based upon our sales volume. However, by 2015, neither of us ranked in the Top 20 among cooperatives anymore, despite doing financially fabulous.”

More recently, in January 2017, two other cooperatives — Valley Agronomics LLC, Rupert, ID, and Wilco-Winfield, Mt. Angel, OR — took part in a merger for this very same reason. According to Valley Agronomics CEO Dave Holtom, the companies were hoping to not only expand their geographic and crop diversity, but “remain relevant” within the cooperative marketplace.

Pressure from the Supplier Chain

Recently, say many experts, another big reason for the rash of cooperative mergers comes from market forces higher up the supply chain — namely, the host of mergers now taking place among crop protection products/seed companies. In the past year alone, Syngenta and ChemChina and Dow and DuPont have formally merged their operations. Next up is a pairing of Bayer and Monsanto, possibly being completed with governmental regulatory sign-off by the end of the year.

According to W.M. (Jim) DeLisi, Owner of Fanwood Chemicals, this consolidation in the supply chain has promises to depress the already razor-thin margins on products that many ag retailers have been dealing with for the past few years. “There has also been significant consolidation [among retailers] as they are all under severe price pressure,” said DeLisi, speaking at the AgriBusiness Global Trade Summit in Las Vegas, NV, in August. “There will also be mergers of producers and distributors to try to squeeze out costs from the supply chain.”

Finally, another factor in the current cooperative mergers could tie to something a bit more basic altogether, age. “Right now in agriculture, you have a slew of people who are at retirement age and don’t have a clear succession plan in place at their companies,” said Milan Kucerak, CEO of Landus Cooperative, Ames, IA, in a 2015 interview with CropLife. “In these cases, a merger is probably a good option. The difficulty, though, will be finding the right people — ones that can step up from managing millions of dollars to ones that can effectively handle running billion dollar companies.”

However, “just getting bigger” isn’t always the plan when cooperatives do merge. For instances, Landus Cooperative was formed by the 2016 merger of two long-standing Iowa cooperatives, West Central Cooperative, Ralston, IA, and Farmers Cooperative, Ames, IA. This past June, the company announced its Project 2020 initiative, titled Consolidate Then Grow, which sought to reduce the Landus workforce by 5%. To accomplish this, the company was closing four locations and closing/selling several grain assets.

“We are reducing costs and consolidating to be more profitable and, in turn, re-investing profits to more efficiently handle smart volume through strategic assets,” said Kucerak in a press release detailing the plan. “While never easy, we need to make changes in order to move our business forward on behalf of our farmer-owners.”

Market watchers expect this kind of “belt-tightening before growing again” to remain the norm for cooperatives for some time to come. In fact, according to Roger Kienholz, General Manager at Crystal Valley Co-op, Crystal Lake, MN (which recently merged with FCA Co-op, Jackson, MN), the low commodity prices that started this round of mergers among cooperatives looks to have some staying power.

“Most people think the low prices will last up to three years or so,” said Kienholz in a recent interview with a Minnesota newspaper. “I think there will be some accelerated consolidation in the next three years.”

Other sources back up this kind of speculation. According to the USDA statistics on cooperatives in the U.S., the industry can expect another 250 such companies to merge or otherwise disappear from the agricultural landscape by 2020, when there is projected to be approximately 750 such companies left scattered across the country.

According to Heartland Co-op’s Coppess, this is just the new market reality all cooperatives will have to face for the time being. “When you look at farmer spending today, it averages out to approximately 44% of their earned income per year — the same level that it was back in the year 2000,” he says. “At the same time, the cost of doing business for your average cooperative has gone up considerably since 2000 — and that hasn’t come back down as farmer spending has. So in this kind of environment, naturally cooperatives are looking to merge to help curb their expenses. Doing more with less is definitely the new normal.”