Specialist: Residual Herbicides No Match For Wet Soil

Soil-applied herbicides can knock out a grower’s toughest weeds but the chemical products are no match against soggy fields, says Bill Johnson, Purdue University Extension weed specialist.

A wet early spring has made it difficult for crop producers to apply soil-applied, or residual, herbicides to their fields ahead of planting. Producers should not push the envelope on herbicide treatments while fields are holding too much water, Johnson says.

“If it’s dry enough to plant, it’s dry enough to spray,” Johnson says. “We don’t plant our crops when soil conditions are such that we’re dropping the seed into mud, so we don’t want to apply our herbicides onto muddy ground, either.

“We run into challenges when we apply to fields that are too wet. One, we’re going to leave ruts in the field. Two, all herbicides are labeled such that they cannot be applied to standing water anyway. If we want to get the most out of our soil-applied herbicides, we need to put them on in conditions similar to those in which we would plant the crops.”

As their name suggests, soil-applied herbicides are sprayed on the soil before, during or just after crops are planted. While too much water nullifies their effectiveness, most residual herbicides need some soil moisture in order to work properly.

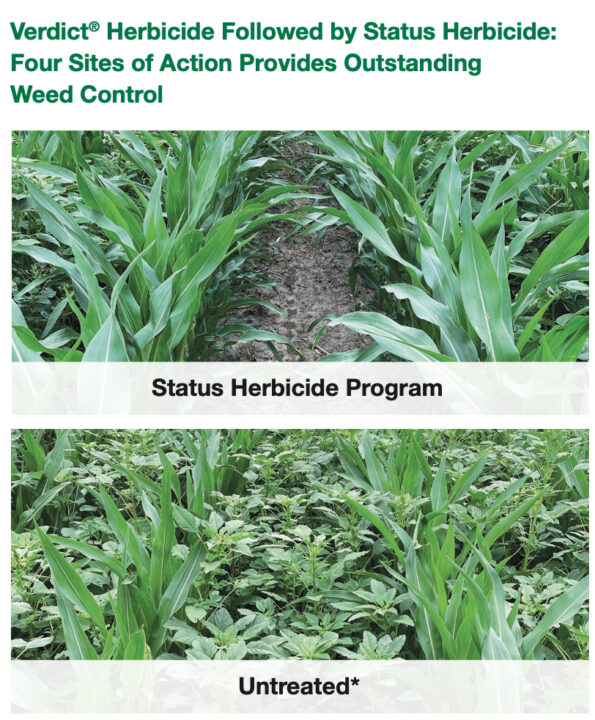

The herbicides are activated by moisture within the soil and are then absorbed by weed seedlings. Weed growth stops or is stunted, leading to plant death shortly after it emerges.

“A residual herbicide will have activity in the soil anywhere from about one to six weeks after application, depending on the product that you use,” Johnson says. “So what you essentially get, then, is herbicide activity that you don’t really see, because you have fewer weeds coming up. The weeds that do emerge from that residual system are going to be a little bit easier to control with your post-emerge herbicides.”

Excessive wetness isn’t the only challenge to using soil-applied herbicides. Johnson say growers should be careful to:

- Choose the right residual product. “You have to know which weeds you’re going after,” Johnson says. “The most effective residual herbicides are going to be matched to the weed species that are in that field. For instance, if you have a giant foxtail weed problem, using a broadleaf herbicide is not going to be of much value in that field. You want to use a herbicide that’s active against grass weeds.”

- Apply at the proper carrier volume. Johnson says glyphosate is one of the few foliar herbicides that works well at carrier volumes of 15 gallons per acre or less, which is why it is often tank mixed with residual herbicides. Contact herbicides, such as paraquat or Gramoxone, require 15-20 gallons per acre, he said.

- Avoid applying in windy conditions, to prevent spray drift.

- Rotate between products and weed control practices, to minimize the development of herbicide resistance.

“More than 90 percent of our soybeans and 70 percent of our corn are glyphosate- or Roundup-tolerant crops, so it’s going to be important for us to treat that technology as an investment,” Johnson said. “We want to keep that technology around for as long as possible, and the way we do that is to minimize selection pressure for glyphosate-resistant weeds.

“Using the appropriate residual herbicide on your worst weed problems and then saving glyphosate for the post-emerge cleanup treatment, is going to be the best way to protect crop yields and slow the development of glyphosate-resistant weeds.”

For more information on weed control in agricultural crops, visit the Purdue Weed Science Web page.

(Source: Purdue University)