Apply Gypsum This Fall For Next Year’s Crop

Brad Brown, a no-till farmer from Center Point, IN, started applying gypsum to his fields in 1986. He applies 1,400 pounds of gypsum every other fall, ahead of corn.

Applying gypsum in late fall is a common practice among crop farmers in order to build soil structure and replenish sulfur for the next year’s crop.

“We first started using gypsum to loosen our clay soils for better drainage and rooting,” says Brown. “Getting sulfur with gypsum gives the next corn crop a boost. It is like a double-whammy!”

With broader availability of synthetic gypsum from power utilities and other manufacturing plants, gypsum application has expanded over the years. According to one industry study, gypsum use among no-tillers has nearly quadrupled since 2008.1

Gypsum (CaSO4 • 2H2O) contains 17-20% calcium and 13-16% sulfur. This equates to roughly 400 pounds of calcium and 320 pounds of sulfate-sulfur for a typical application rate of 1 ton per acre, according to Ron Chamberlain, chief agronomist for GYPSOIL/BRM, a Chicago-based company that markets GYPSOIL brand gypsum.

“Agricultural crops generally need 30 to 70 lbs./acre of sulfur depending on the species,” Chamberlain says.

In the past, farmers like Brown often relied on the “free” sulfur Mother Nature delivered in rainfall. However, as coal-fired utilities and other manufacturing plants have installed modern scrubbing systems to prevent acid rain, atmospheric sulfur deposits have declined. Newer generations of fertilizers and pesticides also supply less incidental sulfur. In addition, higher yielding hybrids remove a great deal of sulfur without replacing it.2

Joe Nester, a crop consultant and owner of Nester Ag, Bryan, OH, routinely discusses the importance of preventing sulfur deficiency with his clients.

“Levels of 10 years ago averaged 30 + ppm soluble sulfur in our soil tests, and today we are seeing levels of 5 to 8 ppm,” Nester says. “These low levels concern us, as sulfur is a secondary nutrient, right behind N, P & K in crop needs. It is also increasingly important as your yields continue to climb.”

In order for plants to benefit from added sulfur, it must be in sulfate form. Gypsum is a ready-made sulfur source for crops, explains Chamberlain. “It goes onto the field with sulfur already in the sulfate form,” he says. Elemental sulfur, on the other hand, requires oxidization by soil bacteria to SO4 or sulfate before it is available. This process also produces acid and drives down the pH.

But what happens to the sulfate over the winter after fall applications of gypsum? Research and practical experience point to strong evidence for gypsum’s staying power.

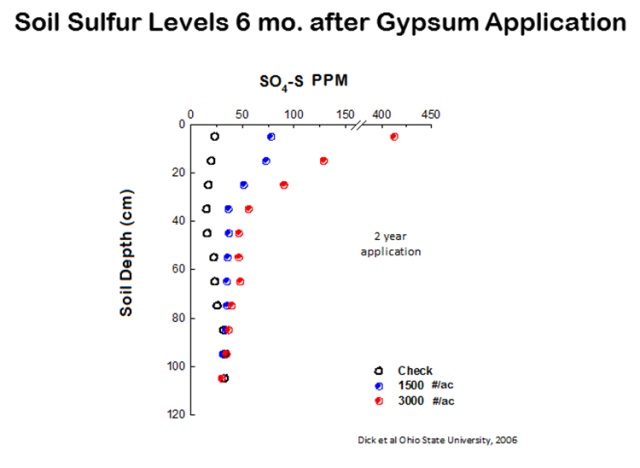

Researchers at The Ohio State University’s School of Environment & Natural Resources demonstrated in a 2006 study that the sulfate in gypsum remains available in the upper soil profile six months after the last application.3 (See chart)

Researchers at the Ohio State University applied gypsum at rates of zero, 1,500 and 3,000 lbs/acre over two years then took sulfate measurements at various soil depths six months after the last application. They observed that 75-420 ppm of sulfate sulfur remained in the upper 8” of the soil.3

Other studies provide additional evidence, including an older study in North Carolina documenting the presence of sulfate-sulfur in a silty clay loam soil 200 days after application.4

“We have noticed nice increases in sulfate levels where we apply gypsum, and those levels are holding at 3x to 4x increases 2 to 4 years after application,” says Nester.

Gypsum doesn’t dissolve all at once, notes Chamberlain. Factors including the source, particle size distribution and the environment surrounding the material once it is applied, all play a role.

“In soils that are common in the Midwest – silt, clay and loam types – the movement of gypsum down through the profile tends to be slower than for sandier soils that are not as common,” Chamberlain says.

With lower commodity prices, one of the big enticements for using gypsum as a sulfur source is cost. Pound by pound, gypsum supplies sulfur at a lower cost than elemental sulfur. “Cost for sulfur in elemental sulfur is six times the cost of sulfur in gypsum at current retail pricing,” Chamberlain says.

It is no wonder why many growers like Brad Brown have settled on gypsum as their sulfur option of choice. “Gypsum is the cheapest form of sulfur we can get and our corn needs sulfur,” Brown concludes.

Download a white paper on gypsum and fall application. For more information, visit www.gypsoil.com or call 1-866-GYPSOIL (497-7645).

References

1. No-Till Operational Benchmark Study conducted by No-Till Farmer, Brookfield, WI.

2. Camberato et al, Soil Deficiency in Corn, Purdue University Department of Agronomy Soil Fertility Update, May 2012. www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/SulfurDeficiency.pdf.

3. Improved Soil Quality and Increased Carbon Credits Through the Use of FGD Gypsum to Enhance No-Tillage Crop Production, Dick et al, April 28, 2006, Ohio State University unpublished report.

4. “Leaching Losses of Sulfur During Winter Months When Applied as Gypsum, Elemental S or Prilled S”, Rhue and Kamprath, Agronomy Journal, Vol 65, No. 4, p 603-605.